Mail

j.niederhauser.schlup@gmail.com

Tel

+41 (0)79 693 28 86

Studio Address

Atelier

Rue du Vallon 2

1005 Lausanne

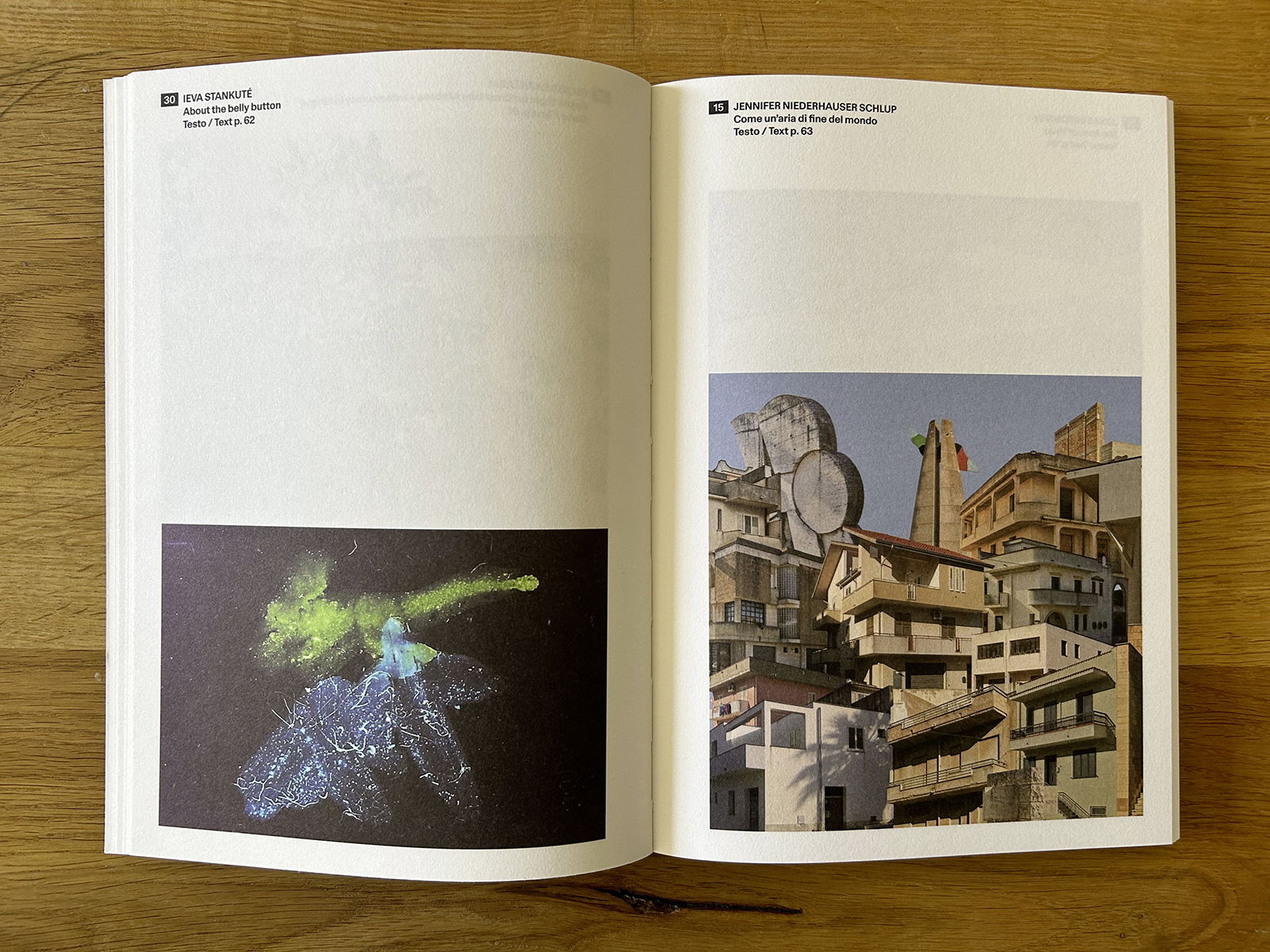

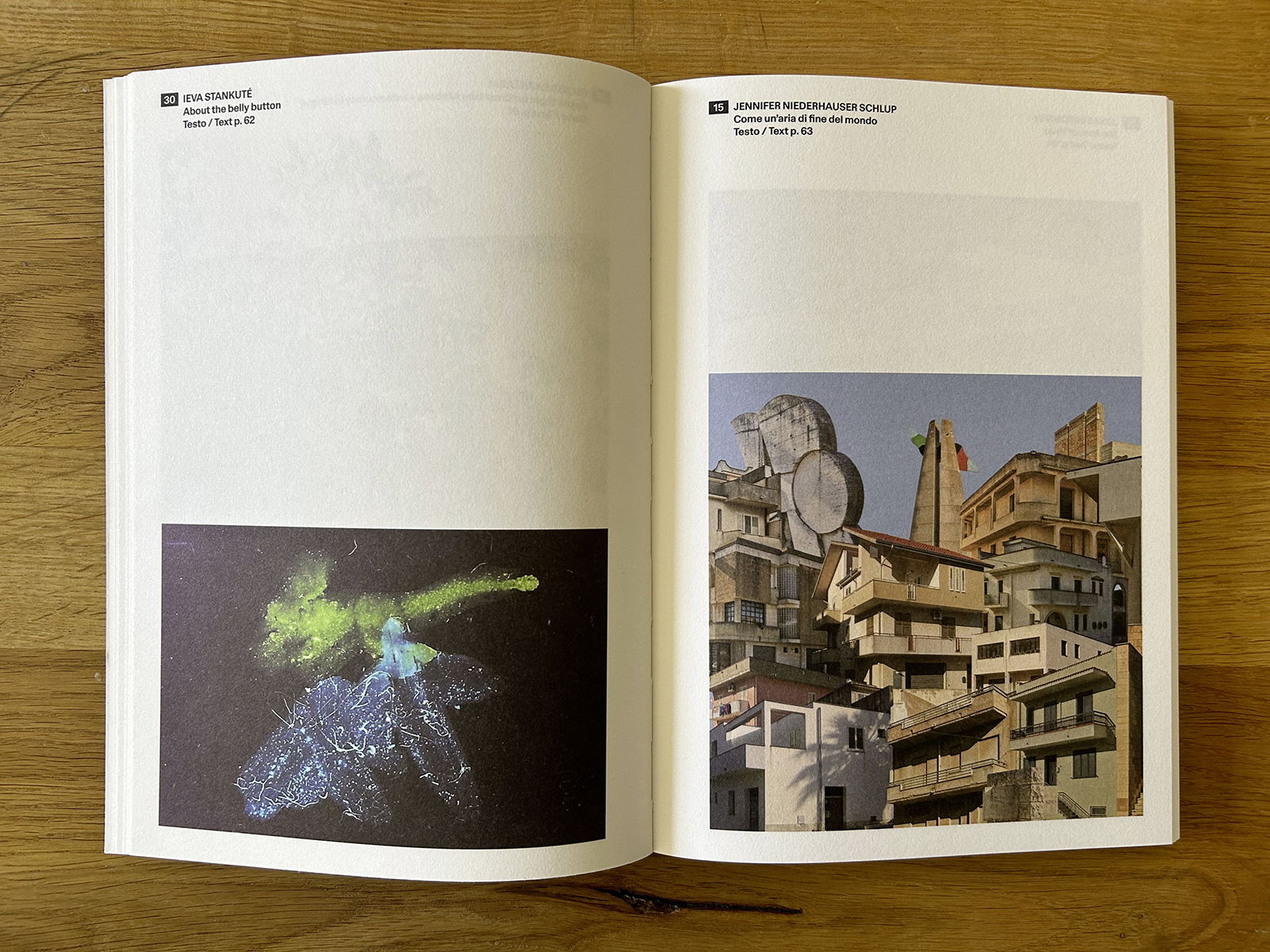

Come un’aria di fine del mondo, Jennifer Niederhauser Schlup, 2023

Sicily is poisonous, terribly poisonous. It burns you with its stunning beauty, then poisons you with its tragedies. So it is with Gibellina, a farming village southwest of Palermo that was struck by an earthquake one night in January 1968 – a disaster with a Pompeii-like feel. When dawn broke in this Belice valley, the village that clung to the hillside had disappeared, shattered under the rubble. Three hundred people died in the first tremor. The survivors had time to flee before the second one, three days later, which buried the carabinieri sent to guard the houses. Once the tragedy was over, the pain gradually subsided, hidden behind makeshift shelters. During the months that followed, seeing no plan for reconstruction, the population seemed to resign itself. Then one day in 1969, a character who seemed to have come out of a novel, nicknamed «il padre di Belice», took over the town hall of Gibellina and its destiny. Ludovico Corrao was a whimsical character. He dreamed of restoring this destroyed city to its former glory by inviting the greatest artists of the moment to rebuild it. He decided to parachute his new city, Gibellina Nuova, fifteen kilometers from the scene of the tragedy. And many art figures were attracted by the lights of his vast project.

The reconstruction came with some difficulties and contradictions as the culture of the victims has been somewhat swept away in the name of a culture that is quite foreign to them. The new way of life of the inhabitants who experienced the earthquake has nothing to do with their previous existence. If they want to return to the place where they were born, they will hardly be able to find their memories. But despite these challenges, the people of Gibellina Nuova have found a new identity and developped a love for this new town.

Moreover, the city offers a fascinating testimony at a time when modern heritage, considered a sub-genre by the authorities, is gradually disappearing. What will remain in the next century of this time when we believed in the monumental and the unreasonable?1

Researching the history of the construction of Gibellina Nuova, I found it almost inevitable to draw parallels with the notion of the Ideal City. Intellectual and material embodiment of utopia, the Ideal City is an urban planning concept aiming at architectural and human perfection. It inspires to build and to make live in harmony a singular social organization based on certain moral and political precepts.

If many «ideal cities» remained only at the stage of dreams in the mind of their creators, some were however completed in the facts. They are however «ideal» realizations in the sense that, contrary to the spontaneous city, which develops little by little according to the needs and thus in an organic way, the ideal city is conceptually elaborated before being materially built, and its foundation results from an intellectualized and unified will. These visions of the social and urban organization of the ideal city are indeed closely linked to notions of Utopia. The quest for the ideal city goes back to antiquity, to Plato’s Republic and before him to the works of Hippodamos in the 5th century BC. But the term «utopia» (which literally means «in no place»), was coined by Thomas More in the16th century. In his work Utopia, the author presents a New World, an ideal city, as being «the best constitution of a Republic».

Thus Utopia is first of all a work of literary fiction with no link to reality, representing an ideal society, opposed to imperfect real

societies. It is a kind of apologue that translates into an ideal political regime, a perfect society or a community of individuals living happily and in harmony.

In this regard one could consider Gibellina Nuova, the «concrete utopia», the catalog city. The recovery of memory and the creation of a new identity through art. But, the existing gap between the conceived city and the practiced city is reminiscent of what Michel de Certeau had described in L’invention du quotidien (1992). For him, technological Reason believes it knows how best to organize things and people, assigning to each one a place, a role, products to be consumed. But the ordinary man silently evades this conformation. He invents the daily life thanks to the arts of making, subtle ruses, tactics of resistance by which he diverts the objects and the codes, reappropriates the space and its use in his way.

Drawing on notions of Utopia and the Ideal City, this project intends to question the spaces we inhabit and people’s interactions with a specific urban environment : in a place, Gibellina Nuova, that has been forced to grow a new sense of community and memories, I want to draw attention to the oblique strategies that are, or can be, developped by a community in the reappropriation of a certain territory. Having photographed individual elements of architecture and sculptures throughout the town — some old, some new, some under construction, some in deconstruction — I have recreated an entirely new panoramic image, which confronts the ideals of the man behind the urban planning of the town and the small cracks that take place when faced with actual daily life. It will be a large scale and immersive display, a kind of mise en abyme of the town itself. A poetic ode to a town that feels a little bite like being on the edge of the world.

1 https://www.admagazine.fr/architecture/balade/diaporama/gibellina-

les-vestiges-dune-utopie/50657